Jason Kelce was unable to fight back tears as he tried to process the journey that led to him sitting inside U.S. Bank Stadium as a Super Bowl champ following the Eagles’ win over the Patriots.

“Persistence has summed up my whole career, summed up my whole life,” Kelce said back in February, pausing and closing his eyes in between sentences to compose himself. “Just keep going, keep moving forward. No matter what obstacle is in the way, just keep moving forward. The resiliency of this team is incredible.”

Kelce and the offensive line had delivered a masterful performance in the Eagles’ 41-33 victory. Nick Foles didn’t take a sack, and the offense piled up 164 rushing yards en route to the title.

There were plenty of times during Kelce’s NFL career when he was unsure if this day would ever come. He’d played for three different head coaches in his first six NFL seasons. The first half of 2016 was the toughest stretch of his career, and he thought he might get traded in the offseason. Then there was the phone call to his father, Ed, before the Super Bowl season started.

Ed can’t remember if it was the second or third preseason game, but the first-team offense was struggling. He hates watching his sons — Jason and Travis, tight end of the Kansas City Chiefs — play in the preseason. The whole time, he’s just hoping that the boys don’t get hurt. Kelce came out of the game healthy, so Ed considered it a success and went to bed. At about 12:30 a.m., his phone rang. It was Jason.

“He starts going into this spiel,” Ed recalled. “‘This was so bad today. I don’t have to do this. I got enough money saved.’ He says, ‘I could live very well and never work another day in my life.’ And that’s probably true because he doesn’t buy stuff. He invests, he saves.”

Ed had received calls like this before from his eldest son. Sometimes, Kelce just needed to vent, so Ed barely said anything during the 45-minute conversation. Kelce wondered aloud whether this was going to be another disappointing season like the previous two, whether the team was good enough to improve on its 7-9 record in 2016.

But then he shifted and explained how he thought the offensive line had a chance to be special. He liked the potential of the wide receivers and the running backs. He thought Carson Wentz had a chance to be special. Kelce then moved on to the defense. Fletcher Cox was in amazing shape, and Jim Schwartz was an excellent defensive coordinator. The linebackers were talented, and while the secondary was young, those guys had a great leader in Malcolm Jenkins.

“He says, ‘I’m thinking this is gonna be another one of those seasons where we’re fighting, fighting, fighting and just miss the playoffs,’” said Ed. “And then he goes and he starts going player by player, going over positions. Forty-five minutes later, he’s like, ‘If everything comes together, this could be a really special team.’ I said, ‘That’s good, that’s good.’ He says, ‘All right, I gotta go now, pops.’ I said, ‘That’s fine, good night.’”

Ed brought that conversation up to Kelce during the Super Bowl afterparty, and his son had no recollection of it. To this day, Kelce admits it must have happened, but he can’t remember picking up the phone.

“I have a lot of those calls with either my dad or my mom. I talk to my wife a lot,” Kelce said. “It’s a very frustrating game. There’s so many little details that can make the difference.”

At 30, Kelce became a Super Bowl champ in his seventh NFL season. Before the championship parade, he asked the organization if he could address the crowd. He had something to say. Now and forever, Kelce in his Mummers costume will be the lasting image that most Eagles fans have from that day. They were singing along and chanting and laughing and hugging — as Kelce delivered zinger after zinger.

But the journey that led to that moment was one filled with anger and frustration — a feeling inside Kelce that people didn’t respect him, that he had to fight for everything he wanted. There was an inner rage he had to channel just to get an opportunity — first in college and then in the NFL.

Jason Kelce won a Super Bowl with the Eagles in his seventh NFL season. (John David Mercer / USA Today Sports)

Kelce still isn’t exactly sure where the anger came from.

He remembers a neighbor picking on him when he was young and his dad telling him to stick up for himself. When the family moved to Cleveland Heights, Ohio, Kelce tried to make friends but sometimes felt like an outcast. He was an excellent athlete and played a level up in baseball. As the youngest on the team, though, he was on the receiving end of some youthful ribbing.

“What I perceived at the time were these guys making fun of me,” said Kelce, who has spoken to sports psychologists and received counseling. “I was always kind of like the brunt of the joke. Now I understand it was just busting balls. Basically, every time that I have an outburst, I always have the feeling of being disrespected. And it’s a perception. I think it really roots itself in my father telling me to always stand up for myself. And that wasn’t always the reality, if that makes sense. It was just something that in my head, the moment I felt like I wasn’t being respected, the moment I wasn’t being treated fairly, I would make sure that didn’t happen again.”

Kelce was suspended nearly every year in elementary school for fighting. By middle school, he had the reputation as “that crazy Kelce kid,” according to his mom, Donna. So people stopped pushing his buttons. Travis, his younger brother, had a much easier time.

“He was lucky because they were all afraid of Jason so they left Travis alone,” Donna said. “(Jason) wasn’t a bully. Never, ever. He was always the one that was helping the kids out that didn’t have any chance to fight for themselves.”

As he got older, Kelce was able to take his aggression out through athletics. He was a star linebacker at Cleveland Heights High School and also played hockey and lacrosse while playing the saxophone in the jazz band. As a sophomore, Kelce started drawing interest from various colleges. He thought it was a foregone conclusion he’d play football in college. But when it came time for programs to hand out scholarships, Kelce didn’t get a single offer.

He had never committed to a full-time football offseason program because he was always playing other sports, so there were questions about his size and strength. His senior year, Kelce had to decide: Play at a I-AA or Division II school or try to walk on at a Division I program.

“My parents almost pushed me to go to a Division I school,” Kelce said. “I think they both knew that’s what I wanted to do. And I think they both had a lot of confidence that I could do that. Maybe they didn’t, and I didn’t know it at the time. They never even hinted that they didn’t think I could play Division I football.”

Around this time, Kelce’s grandfather, Donald Blalock, gave him a card that included a quote that was attributed to Calvin Coolidge.

“Nothing in this world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not: nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not: the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent. The slogan ‘Press On’ has solved and will always solve the problems of the human race.”

Kelce is not big on motivational sayings or inspirational quotes, but this one stuck with him. He kept the card in his wallet, never losing sight of the message.

When Kelce was growing up, Blalock lived in Sioux Falls, S.D., and wasn’t around a lot. But he liked to write letters and pass along helpful messages. He would have loved to be at the Super Bowl, but physically, it would have been difficult. Instead, he watched on TV and afterward saw Kelce recall the Coolidge quote that meant so much to him.

Earlier this year, Blalock died at 87. During the Eagles’ bye week, Kelce joined his family in Vermilion, Ohio, to scatter his grandfather’s ashes.

“It was an emotional weekend,” said Donna. “But he hung in there and he saw Jason win the Super Bowl. And he was with it enough to know exactly what happened and everything. And he heard the comments Jason made about him. It came full circle. And it was awesome.”

De’Angelo Smith remembers seeing the broken window near the training room at Cincinnati.

Kelce didn’t understand the concept at the time. He arrived at the University of Cincinnati in 2006 already feeling slighted as a scholarship-less walk-on. Before a practice, he waited in line for about a half-hour to get his ankles taped. Smith was a veteran on the team and a scholarship player, so he cut in front of Kelce and got taped first. Kelce didn’t like that, so he took out his frustration by shattering a nearby window with his fist. The next day, there was a sign-up sheet for everyone who wanted to get taped up.

“He actually won the deal because he got the sign-up sheet and I couldn’t jump the line anymore,” Smith said with a laugh.

“Just something as simple as that,” Kelce said. “But to me, it was like, ‘Why is this guy not respecting me? What’s the problem here? He’s not showing me (respect).’ But, and this is the problem, this is something I was talking to my mom about at Thanksgiving, in my head, it was always justified. And when I talked to my parents about it, it was always justified. But in my head wasn’t always what reality was. This guy who cut, De’Angelo Smith, was a veteran player. And that was kind of the understood rule. It wasn’t like he was picking on me as a personal attack. This was just a veteran saying, ‘I’m playing so I get to go in front of you in the tape line.’ There was always a reasoning in my head — not that that justifies anything. And I still struggle with it.”

Kelce had no interest in being the stereotypical walk-on — just along for the ride, might get a few meaningless snaps. He was out to destroy anything in his way. He wanted to make sure the coaches noticed him.

Kelce remembers practicing against a high-profile recruit named Freddie Lenix. Every time they took the field, Kelce was obsessed with proving he was a better player. He wanted to show that he deserved to play and receive a scholarship.

“Being a walk-on’s different,” he said. “I didn’t really feel like I deserved anything. I really feel that being a walk-on probably humbled me in the best way possible. It really forced me to have a realistic look at maybe I’m not good enough. Maybe I need to work harder to be better.

“Really, a lot of guys I don’t think liked me that much. I think guys liked me and respected me, but I know a lot of guys hated me for the way I practiced for sure. I had to try and do something to stand out, in my mind. I didn’t want to just be like the other walk-on guys that were just tackling dummies. If I was out there, I wasn’t just gonna just be some guy that you were gonna push around. That wasn’t the way it was gonna happen. And the coaches kind of revved that into us, too. I really took that to heart.”

Strength and conditioning coach Paul Longo believed Kelce should make the switch from linebacker to offensive line. Brian Kelly’s staff previously coached at Central Michigan, where it had moved Joe Staley from tight end to offensive tackle. The coaches felt Kelce would be a standout athlete at guard or center, and had the demeanor for the positions. They ended up being right. Longo helped Kelce add muscle and weight. He made the transition, starting 38 games in his college career — 26 at left guard and the final 12 at center.

“Offensive-line play made sense to me,” Kelce said. “I never was really a good SAT guy. I’m really slow at reading so I don’t do good with timed tests. I don’t even know what my Wonderlic was. It was probably very average. But one thing I’ve always been really good at, and I still remember a teacher telling me when I was in second grade, I’ve always been really good with like, puzzles and patterns. I’ve always been really good with like, spatial awareness and being able to pick out little itty, bitty differences in things. That’s, I think, more applicable for a football player than some other intellectual test. I kind of always have been good at that for whatever reason.”

While Kelce was making a successful transition to offense and giving himself a chance at the NFL, the temper still got the best of him at times.

One Friday morning, the coaches split the roster into two teams. Players had to do wall-sits next to each other. They had a 2×4 resting on their laps, and a coach would walk across it. One player at a time would run a relay circuit while the others continued the wall-sit. Kelce’s team was losing, so he decided to do something about it. When it was his turn to run the circuit, he crossed paths with a player from the opposing team.

“I come running across the turf and instead of just running and getting back in line, I just completely decleat the other guy on the other team who’s running across,” Kelce said. “You kind of crossed, but you weren’t really supposed to hit each other. This is just a race. But there weren’t really any rules established.”

Kelce credits Longo and Cincinnati offensive line coach Jeff Quinn for his success, but Quinn knew about the temper and would push his buttons. During one practice, not liking what he had seen, Quinn started testing Kelce, questioning whether he was good enough, whether college football was the right path for him. Kelce snapped.

“I would lean hard on Jason, and so I really got after him,” Quinn said. “And he just, God, he lost his mind almost. And he rips his helmet off. Thank God he didn’t hit me with his helmet. But he whipped it like 25 rows up. … He just whips it, and I’m sure there were a few choice words that came out of his mouth. And we were all kind of a little bit stunned and shocked. I told him, ‘You get your ass up there and you go get that damn helmet.’ That was one of those moments.”

Said Kelce: “I’ve always had a bit of a (temper), and I’ve gotten better with time, this anger and aggression has always been something that I’ve had. And as I’ve gotten older, that’s gone away more and more. I used to have, back in high school, really bad problems controlling it in sports. Besides maybe elementary school, in elementary school, I would get into fights. But I never really got into fights outside of sports. I kind of used sports to get this aggression and youthful energy out of my system. But there was like, a switch. Not always the best thing, for sure. I’ve done some very stupid things that I’ve had to apologize for. I remember a coach in college telling me, ‘What you did, I lost all respect for you.’ I’m not trying to play this up. This is probably one of the biggest problems I’ve had with myself. I’ve seen counselors for it and stuff. I think it’s gotten a lot better for sure. But every once in a while, I’ll have — it’s basically a temper tantrum is what it is.”

Somewhat of a breakthrough came in college, when Kelce talked to a sports psychologist. He realized that most of the incidents involved friends, teammates or coaches — people whom he respected. That was the issue. He couldn’t understand why people he respected, in turn, disrespected him.

The issues never seemed to surface in games. During his NFL career, Kelce has never been called for a late hit or unnecessary roughness. The only personal foul on his entire résumé is a face mask, which happened once.

“They almost never happened in games, and they never happened with people that I didn’t know or didn’t have a relationship with,” Kelce said. “That was the underlying thing. In practice, you have more time to process these feelings of disrespect. And then, not to mention that in practice or with people that you know, you have an expectation through those relationships that they’re going to treat you with respect. If it’s somebody that you don’t know, you don’t really have that expectation. You know what I mean? It really took getting to know that. That’s when I started to understand that mechanism better.

“I didn’t go into the games with the feeling that I was going to be treated with respect. You go into a game, you’re going into a fight. I have no expectation of a level of respect, whereas in practice, when my coach is yelling at me for God knows what, and it’s not in a respectful way, well, this guy should have respect for me. I’m out here busting my ass every single day with him, and I’m working hard, and he’s talking to me like this? So that’s why it almost never manifests itself in games.”

When Kelce signed a six-year, $37.5 million contract in 2014, Quinn was the second person he called after his parents to say thanks.

“Those are incidents. Those are not who Jason was,” Quinn said. “You could never have enough guys like Jason Kelce in your foxhole. Could never. Those guys are at a premium. They are special.”

Jason Kelce attends a Cincinnati-Temple game in October in Philadelphia. (Chris Szagola / AP Photo)

When former Eagles offensive line coach Howard Mudd was tasked with watching prospects before the 2011 draft, he couldn’t take his eyes off of Kelce. The scouting community dinged Kelce for his size, but Mudd didn’t care much. He focused, instead, on the balance, leverage and range. Kelce had all of those things.

On an official pre-draft visit with the Eagles, the organization asked him about the issues he’d had in college with his temper. Kelce was accountable for his mistakes, and that was all Mudd needed to hear. He wanted an athletic center, and Kelce reminded him of a player he coached with the Colts: Jeff Saturday.

When the draft got to the fourth round, Mudd started pestering then-head coach Andy Reid to take Kelce.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry, we’re gonna get him,’” Mudd said. “‘I promise you, we’re gonna get him.’”

When the fifth round came, Mudd got on Reid again, but it still wasn’t time. At this point, Kelce was hoping to make it to undrafted free agency. He’d hit it off with Reid and Mudd, and wanted to sign with the Eagles. But the team ended up drafting him in the sixth round with the 191st overall selection.

When the team started practicing in the summer, after the end of a lockout, it wasn’t long before Mudd eyed Kelce to be the starter. Reid thought Mudd’s plan might be too aggressive, but finally, in the preseason, Mudd convinced him to give Kelce a shot after the first series.

“He will be able to handle the mental part and the psychological part,” Mudd told Reid. “He’ll be able to make the calls, and he won’t shit his pants. Well, yes, he will, but no different than anyone else. When he messes up, he’s not gonna go to shit.”

Jason Kelce on the sideline during a preseason game in 2011. (Michael Perez/AP Photo)

Kelce started all 16 games as a rookie and has started 106 games overall since 2011. In his second season, Kelce suffered a knee injury and played in only two games. Reid was fired after the season. In 2015, the Eagles went 7-9, and owner Jeffrey Lurie fired head coach Chip Kelly.

Everything came together in 2017 with the 13-3 season and the Super Bowl title.

Kelce has long been a favorite of Eagles offensive line coach Jeff Stoutland. Stoutland often praises Kelce’s football intelligence and still marvels at the key in-game adjustments the center made against the Patriots in the Super Bowl.

“They had a linebacker on one side, and he ran over at the last second,” Stoutland said. “LeGarrette Blount ran to the right on a mid-zone play. Between Kelce and (Stefen Wisniewski), there was a conversion call. Now we had talked about these calls prior, but they ran over late and they ran a blitz, and we brought the whole line in unison. And LeGarrette really, he did a great job of reading it and he went off to the right untouched, down the sideline. It was a big play in the game. That was not something we had done during preparation for that game.

“He’s so smart and sees things. Visually, he sees things. He sees safety rotations. He’s a quarterback playing center.”

In the days following the Super Bowl, Kelce couldn’t sleep.

Fans get to enjoy the run as it happens. But for players and coaches, there’s always the next practice or the next game. Kelce celebrated like everyone else, but it wasn’t until days later that he realized what had happened. Then he started to think about his personal journey: From being a walk-on to getting drafted in the sixth round to the disappointing seasons, the injuries and the trade rumors.

Kelce thought about everyone else’s respective journeys — the other offensive linemen, Nick Foles, the coaches. That’s when the seeds of the parade speech began to get planted in his head. To this day, his wife, Kylie, is the only person who’s heard the raw, uncensored version.

The morning of the parade, Kelce made sure to eat a big breakfast. The players were told not to bring their own alcohol on the busses (not everyone followed the rules). Once Kelce, decked out in his Mummers costume, saw how quickly they were moving, he decided to get out and walk the route.

“I got out of the bus right away, pretty much ran down the entire length of Broad Street, grabbing beers from anyone who would offer them and chugging them,” Kelce said. “I would be lying if I said I knew the count, but it was certainly north of 20. It was a lot.”

He’s a big guy with a high tolerance, so on a scale of one to 10, Kelce put his drunkenness at a five. He wanted to make sure he could deliver the speech.

Kelce didn’t write anything down, but he knew the topics and the people he wanted to reference. He saw a connection between his story, the team’s story and the city’s story. Kelce spent much of his football life fighting for respect. He felt like Philadelphia was always doing the same thing.

Finally, everyone had earned it. Finally, they could be called champions.

“I think the speech gets misunderstood a lot,” he said. “People think that I’m criticizing the media or that I was saying everybody was wrong with all these narratives. But that’s kind of not what it really was. It was more that these are all things that people had to endure or persevere through to get to the ultimate team championship.

“The whole speech and the whole season, my story and everything, ultimately it really correlated with Philadelphia’s story. And I think that’s why it was such a special season and that speech resonated with so many people.”

News

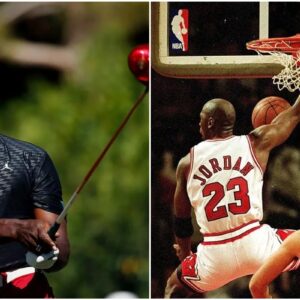

“I didn’t love MJ, and I thought MJ was difficult and unnecessarily harsh on his teammates” – Luc Longley’s true feelings about Michael Jordan

One of the glaring omissions in the famous Chicago Bulls documentary “The Last Dance” was the absence of prominent Center Luc Longley in the 10-part series. Longley was an integral figure of the Bulls’ second three-peat between 1996 to 1998,…

Michael Jordan Would’ve Been Destroyed if Cleveland Hadn’t Made Their Potentially Biggest Mistake, As Per 3x NBA Champion

Michael Jordan didn’t have the easiest path to becoming a champion. The Boston Celtics and the Detroit Pistons were the two major obstacles His Airness overcame to claim his first NBA championship, but what if he had failed at an earlier stage…

Michael Jordan Suffered From a Painful Condition That Only 10% of American Adults Have, Ex-Nike Executive Reveals Shocking Details

It’s no mean feat to create a legendary career on and off the court, but Michael Jordan did it, thanks to his hooping skills and the iconic collaboration with Nike. His retirement from the game has been two decades yet the Jordans…

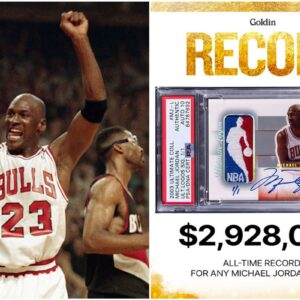

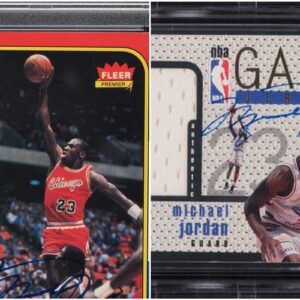

Michael Jordan card sells for record-high price

A rare autographed Michael Jordan Logoman card sold for $2.928 million, the most ever paid for a Jordan card. Credit AP Photo/John Swart An autographed Michael Jordan Logoman card sold for $2.928 million on marketplace Goldin. The card, which is the most…

Michael Jordan sports card sets new auction record

A sports card of basketball great Michael Jordan recently sold at auction for nearly $3 million. 🚨 BREAKING: there is a NEW ALL-TIME HIGHEST-SELLING MICHAEL JORDAN CARD 🚨 Final Sale Price on the 2003 Upper Deck Ultimate Collection Michael Jordan…

Michael Jordan Opens Up For The First Time About His Billion-Dollar Business: ‘i Made 4 Times More Than My Entire Nba Career

**Michael Jordan Opens Up for the First Time About His Billion-Dollar Business: ‘I Made 4 Times More Than My Entire NBA Career’** Basketball legend Michael Jordan recently opened up about his incredible success off the court, revealing for the first…

End of content

No more pages to load