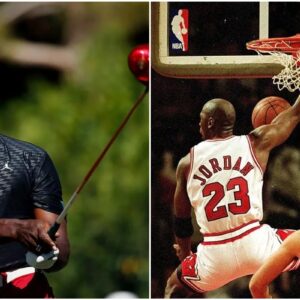

Michael Jordan or LeBron James? It is one of the essential questions in the modern era of sports fandom, encompassing facts and biases, statistics and anecdotal evidence, and the ever-shifting barometer of cultural relevance. It turns friends into foes, barbershops into the site of parliamentary debates, and the Super Bowl LII champions into bickering schoolchildren. The question of Jordan or LeBron may live on for longer than they do. So, before we fully gear up for what should be a frenzied second half of the season, why not celebrate and examine the impact of two of the most influential players in basketball history?

Welcome to Jordan-LeBron Week.

In December 1986, Michael Jordan dunked on Tree Rollins. It happened quickly and without warning, like a spider bite or a bird pooping on your head (both of which, I suspect, would’ve ultimately been less embarrassing for Rollins to experience). Jordan had the ball out near the left bend of the 3-point line and was surveying the court. There were three defenders nearby, two of whom were especially concerned with him. He pump-faked a pass to Charles Oakley, who was at the nearest baseline, and Cliff Levingston, one of the aforementioned defenders, stumbled backward from the feint, falling down, and let me explain something real quick:

It’s true that Jordan was at the beginning of his third season in this particular moment, and also that he’d lost basically all of his second season to a broken foot. But he’d already established a reputation as a devastating offensive threat. I mean, just consider these three things: (1) To that point of the season, he was averaging an absurd 38.8 points per game, including a 50-point explosion on the Bulls’ opening night. (2) He had scored 40 or more points in his previous seven games and would go on to score 40 or more in this game and the next, bringing the total to nine in a row, a run only ever bettered in NBA history by Wilt Chamberlain. And: (3) Beyond just the nine straight games of 40 or more points, he’d also go on to do it 15 times in 20 games. And so if you ask, “Why would Cliff Levingston fall down simply from a faked pass?” I would respond, “Because it was Michael Jordan who was faking it, and everything Michael Jordan was doing with a basketball at that time was fucking terrifying.”

So: Levingston stumbled backward, falling down, and it created a direct path to the basket for Jordan. Jordan took one dribble and gathered the ball, and as he did, Rollins, a 7-foot-1 center of monumental girth and mass, slid over to protect the rim. They both jumped and prepped their nuclear missiles at the same time, and, all things considered, Tree appeared to have the advantage, what with him being seven inches taller and 20 or so pounds heavier than Jordan. But then he didn’t.

Jordan mashed it home on him, and it was so surprising that he’d done so that two things happened, one of which was small and has happened many times since, the other of which is bigger and hints at why I’m telling you this story.

The small thing: The crowd cheered. Loudly. And the reason that’s noteworthy is because the game was being played in Atlanta, not Chicago. Imagine that. Imagine a man comes into your home, karate kicks you in the teeth, and then your family is so impressed by the move that they start cheering for him. “Whoa, great kick,” they tell him as you feel around under the couch, searching for your incisors and also your pride.

The bigger thing: When the dunk went in, the force of the shockwave knocked Rollins sideways. As he gathered his balance, Oakley, who had moved into the paint during the play, reached back and put his finger right in his face. It was, in a manner of speaking, a disrespectful exclamation point on the end of the play. Here’s a screenshot of the moment:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58767261/shea_mj_supporting_cast_getty_ringer_2.0.jpg)

Jordan is on the left of Rollins, scowling at him, very clearly making a “Bitch, I told you don’t jump” face, and there’s Oakley on the right, very clearly doing a “Bitch, he told you don’t jump” finger point. They turned Rollins into the sliced meat of a 7-foot-long BITCH, DON’T JUMP sandwich, which is the worst kind of sandwich you can be turned into on a basketball court.

I mention this specific play because it represents the main idea of this article: that many of the players who were in the NBA during Jordan’s reign would go on to exist, at least in part, less as their own entity and more as a character in Jordan lore. Both Tree Rollins and Charles Oakley are that here; Rollins ended up becoming The Guy That Jordan Dunked On and Oakley, a devastating cheerleader, ended up becoming one of Jordan’s Guys, a small group of players he held extremely close. (One of my favorite Jordan stories: After the Bulls traded Oakley to get veteran Bill Cartwright, Jordan, who very much did not approve of the trade, spent the following days throwing impossible-to-catch passes at Cartwright so he could complain about how Cartwright couldn’t catch them. All I want is a coworker who cares enough about me to sabotage whoever it is that comes in after me when I get sent off to work somewhere else.)

Have you seen Mean Girls? It’s about a girl who shows up at a new school and infiltrates the school’s most popular group of girls (“The Plastics,” as it were). The Plastics are led by Regina George, held up around campus as the physical manifestation of teenage perfection. As a way to establish the dominance that Regina George holds over her high school, other students share different rumors about how incredible and overwhelming she is. “Regina George is flawless,” says the first girl. “I hear her hair’s insured for $10,000,” says the third person. “I hear she does car commercials … in Japan,” says the fourth person, and I don’t know why the “in Japan” part is so goddamn funny but it is. And it goes on and on like that. Then the very last person says, “One time she punched me in the face … it was awesome.” That’s how incredible Regina George is: so incredible that being punched in the face by her is a mark of prestige because being punched in the face by her means she had to, at least in that instant, acknowledge that you exist.

That is, in a sense, what I’m talking about with Jordan here; it’s a kind of eternal stamp, really. There’s a whole list of people who, for one reason or another, have forever become associated with him. And it’s a spectrum of influence that stretches all the way from Well, This Is Very Terrible to This Is Great.

All the way on the Well, This Is Very Terrible end, for example, is Kwame Brown, and I’m going to start with him because he had a quote in 2010 in which he explicitly references what you and I are talking about in this article.

A quick summary of the Kwame-Jordan history: Jordan was the head of basketball operations (and soon to be a player, lol) for the Wizards when they selected Kwame with the no. 1 pick in the 2001 draft. During Kwame’s time with the Wizards, there were multiple reports of Jordan bullying him, some instances of which were so crushing that they moved Kwame to near tears. (You can read all about it in this excerpt of Michael Leahy’s book about Jordan’s final run with the Wizards.) Kwame eventually denied the allegations, and even if he was telling the truth (it definitely felt like he was) it didn’t matter. The allegations were enough; they stuck to Kwame’s name forever.In 2010, the Charlotte Bobcats signed Kwame to a one-year deal. Jordan was a majority owner of the Bobcats then, and so of course people asked Kwame about their past history. That’s why he told Michael Lee of The Washington Post, “We’re always going to be linked. I might as well come here, right?” Kwame knew then what I’m telling you now: When Michael presses his fingerprints down onto your heart, they’re not so easy to wash off.

(Kwame is a very extreme example of this. Other sad ones that are less biting: Muggsy Bogues, who Jordan one time backed off of during the final seconds of a close playoff game and allegedly shouted, “Shoot it, you fucking midget,” a double insult so damning [not to mention offensive] that Bogues later said it ruined his career; Sam Bowie, who remains tied to Jordan because he was drafted by the Trail Blazers one spot before Jordan was chosen by the Bulls; any of the guys Jordan prevented from winning a championship when he was playing, including but not limited to Patrick Ewing, Clyde Drexler, Charles Barkley, and Karl Malone; and any of the guys who Jordan hit an iconic shot over or had an iconic dunk on, including but not limited to Bryon Russell, Craig Ehlo, and the two Monstars who were holding onto him when he did the half-court dunk in Space Jam.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10268925/298697.jpg.jpg)

The opposite version of the Kwame story is what happened with Steve Kerr, who played with Jordan for three seasons. Just a few months into their relationship (this was during the run-up to the 1995-96 season when the Bulls would finish a record-breaking 72-10), Kerr and Jordan got into an argument during a scrimmage that turned into a fistfight. Kerr later said that the fight seemed to make Jordan respect him. Here’s a good bit about it from a story ESPN ran about the punches in 2013:

There was mutual respect, with Kerr feeling that Jordan trusted him on the court more in important situations. In Jackson’s new book, “Eleven Rings,” he says the punch was a wake-up call for Jordan and a turning point for the championship-winning 1995-96 Bulls who won 72 regular-season games, a record that will likely never be broken. Who knows what the wake-up call would have been if the fight never took place? Who knows if there even would have been one?

“It made me look at myself, and say, ‘You know what? You’re really being an idiot about this whole process,’” Jordan says in “Eleven Rings.” He realized he hadn’t gotten in sync with his new teammates after coming back from his baseball sabbatical.

(Kerr, who now has two championships and broke the 72-10 record as a head coach, is a very extreme example of the This Is Great end. Other happy ones that are probably less historically profound: John Paxson hitting the 3 at the end of Game 6 that helped the Bulls win their 1993 championship and going on to serve as the general manager of the Bulls from 2003 to 2009; the flu, which had a horrible reputation for all of history until Michael Jordan’s Flu Game in 1997, at which point the flu somehow became an actual cool thing to have; and Phil Jackson, who showed up to Chicago as a suit jacket on an upside-down hanger and left Chicago with six championships and Greatest Coach of All Time considerations.)

I think the most curious case of the Jordan effect is Scottie Pippen. He was a wildly talented player and also a wildly important player. And it’s hard to imagine that Jordan ever would’ve wound up becoming the highest grade of basketball royalty without Scottie running along next to him. (Now seems like a good time to remind you that Jordan never even made it out of the first round of the playoffs before Pippen arrived, let alone won a championship.) And so, in that respect, it feels like it’s a slight that the highest acclaim ever given to Pippen was that he was just a very, very, very good second-place player on his team. ON THE OTHER HAND, THOUGH, it feels equally weird to argue that Pippen would’ve ever grown his shadow 100 miles wide like it is now if he’d not had Jordan running along next to him. (Now seems like a good time to point out that Pippen’s best playoff run without Jordan, which came with the 2000 Blazers and lasted all the way up to Game 7 of the Western Conference finals, ended up crumbling because it looked like nobody on the team wanted to do what it was that Jordan felt so comfortable doing: close out a game against a deadly, attacking opponent.) So I don’t know. I don’t know how to play that.

What I do know is that only Jordan’s unique brand of greatness allows for this kind of discussion (LeBron, I believe, will get here, too). Because it transcends the expiration date of traditional stardom. It creates an everlasting life, of sorts. Whether a player wants it or not.

News

“I didn’t love MJ, and I thought MJ was difficult and unnecessarily harsh on his teammates” – Luc Longley’s true feelings about Michael Jordan

One of the glaring omissions in the famous Chicago Bulls documentary “The Last Dance” was the absence of prominent Center Luc Longley in the 10-part series. Longley was an integral figure of the Bulls’ second three-peat between 1996 to 1998,…

Michael Jordan Would’ve Been Destroyed if Cleveland Hadn’t Made Their Potentially Biggest Mistake, As Per 3x NBA Champion

Michael Jordan didn’t have the easiest path to becoming a champion. The Boston Celtics and the Detroit Pistons were the two major obstacles His Airness overcame to claim his first NBA championship, but what if he had failed at an earlier stage…

Michael Jordan Suffered From a Painful Condition That Only 10% of American Adults Have, Ex-Nike Executive Reveals Shocking Details

It’s no mean feat to create a legendary career on and off the court, but Michael Jordan did it, thanks to his hooping skills and the iconic collaboration with Nike. His retirement from the game has been two decades yet the Jordans…

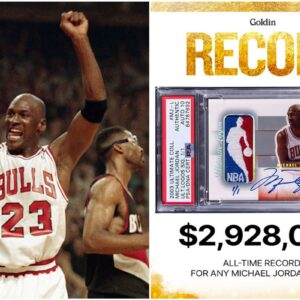

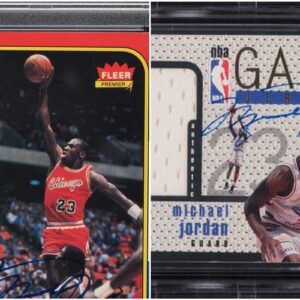

Michael Jordan card sells for record-high price

A rare autographed Michael Jordan Logoman card sold for $2.928 million, the most ever paid for a Jordan card. Credit AP Photo/John Swart An autographed Michael Jordan Logoman card sold for $2.928 million on marketplace Goldin. The card, which is the most…

Michael Jordan sports card sets new auction record

A sports card of basketball great Michael Jordan recently sold at auction for nearly $3 million. 🚨 BREAKING: there is a NEW ALL-TIME HIGHEST-SELLING MICHAEL JORDAN CARD 🚨 Final Sale Price on the 2003 Upper Deck Ultimate Collection Michael Jordan…

Michael Jordan Opens Up For The First Time About His Billion-Dollar Business: ‘i Made 4 Times More Than My Entire Nba Career

**Michael Jordan Opens Up for the First Time About His Billion-Dollar Business: ‘I Made 4 Times More Than My Entire NBA Career’** Basketball legend Michael Jordan recently opened up about his incredible success off the court, revealing for the first…

End of content

No more pages to load